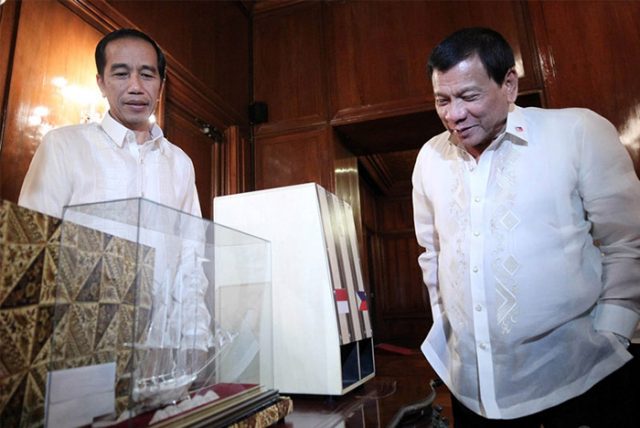

In the past few years, two large democracies in Southeast Asia, Indonesia and the Philippines, have had their share of electoral drama. In 2014, upstart reformist Joko Widodo (widely known as Jokowi) squeaked by former general Prabowo Subianto to win Indonesia’s presidential election. Two years later in the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, a controversial law-and-order candidate, challenged the establishment and captured the presidency.

These elections highlighted a growing anti-establishment and populist mood in the two countries. Less noted was how both Jokowi and Duterte emerged from local politics, campaigned on their accomplishments as mayors of small cities, and gained a following based on the results they achieved in their localities. Little has been written also on their ability to govern based on purely local experience. To what extent does their local experience guide their governance at the national level? Do their local models work as advertised for the national level, and if so, how?

“Jokowi and Duterte emerged from local politics, campaigned on their accomplishments as mayors of small cities, and gained a following based on the results they achieved in their localities.”

Widodo

Joko Widodo became the mayor of a medium-sized city in Central Java in the wake of Indonesia’s democratization and decentralization initiatives in the late 1990s and early 2000s. A furniture exporter by trade, Widodo had little experience with politics before running for mayor in 2004 and winning unexpectedly. As mayor he gained massive popularity for a reformist agenda, which appealed to both pro-poor and pro-investment constituencies. He cracked down on corruption and reduced bureaucratic red tape that hampered investment. At the same time, he implemented healthcare and education policies that expanded access to services for the poor.

How have his local reforms translated to the national level? In some areas, quite well. Jokowi has pursued a pro-poor agenda including a national universal healthcare policy. Although not the mastermind of the national policy, Jokowi has sought to put his own stamp on it, and he has stood by his pledge to make Indonesia the most populous country in the world to offer universal access to healthcare.

He has also placed strong emphasis on Indonesia’s business and investment climate, especially through infrastructure reform. As part of his larger vision, his administration has committed to massive upgrades of infrastructure―including 5,000 kilometers of railway tracks, 3,600 kilometers of roads, 49 dams and 24 seaports―as well as construction of a 35,000-megawatt power plant. Like healthcare, some of these policies were initiated under previous administrations, but Jokowi has sought to push them forward and put his own brand on them.

The limitations of Jokowi’s local experience have become visible in the context of his reformist vision for clean government. When he ran for president, he promised to fill his cabinet with capable technocrats rather than political hacks. Almost immediately after he was elected, however, he was forced to accept the appointment of cabinet ministers who were known to be corrupt individuals as a way to pay political debts to his patrons. Rather than focusing on technocratic effectiveness, he has also dismissed key ministers, shifted others around and appointed new ministers, all with an eye toward co-opting opposition parties and bringing them into his coalition.

“The limitations of Jokowi’s local experience have become visible in the context of his reformist vision for clean government.”

To many observers, Jokowi has abandoned the politics of reform. Some have argued that the cabinet reshuffles were less about his policy agenda and more about positioning himself for the 2019 elections, particularly by distributing cabinet seats to candidates who would have the financial resources to support him.

Duterte

What of Rodrigo Duterte? In the 1970s, Davao was caught between a communist insurgency and the Moro rebellion, so mired in violence that it was known as the “nation’s political assassination center.” As mayor, Duterte transformed Davao into the safest city in the Philippines. One of his policies was to establish security outposts ringing the city, where militias had to surrender their weapons. He also banned public smoking, established a 10 p.m. curfew, and imposed speed limits in the city.

Duterte took a pro-business stance and recruited market-oriented officials in the municipal government. A municipal board was responsible for bringing in investors from the capital city and abroad. This yielded clear results. High-rise condominiums and shopping malls were built, and industrial production expanded. To expedite such projects, Duterte demanded that business permits be processed within 72 hours and that any delays would have to be reported and explained directly to the mayor.

The positive results of such policies were clear. In 2014, Davao’s economy grew 9.4 percent, outpacing the growth rate of any other region in the country.

It is questionable, however, how effective a national leader Duterte has been in almost two years in office. He launched a violent campaign against drug trafficking that has led to a staggering rate of extrajudicial killings, estimated by human rights advocates to exceed 12,000. By comparison, the estimate of extrajudicial killings under the dictatorial regime of Ferdinand Marcos was 3,257 over a 10-year period. Yet there is no clear evidence that drug trafficking under Duterte has declined.

Duterte also promised during the presidential campaign that he would address the problem of weak labor protection in the Philippines. The most critical issue is contract work because employers often fire workers just before they are eligible for full employee benefits. Under his leadership, the Labor Department has stopped firms from repeatedly re-hiring workers under short-term contracts but continues to allow seasonal and project-based contract work.

“Duterte’s calls for bureaucratic efficiency, for expeditious approval of permits and licenses, and for reform of the transportation system have not led to any concrete action.”

His 2016 state of the nation address, held two months after his election, touched on many other issues that remain largely neglected. His calls for bureaucratic efficiency, for expeditious approval of permits and licenses, and for reform of the transportation system have not led to any concrete action.

Final observations

Both Duterte and Jokowi successfully implemented local reform programs, yet their capacity to extend such successes to the national level is less clear. Jokowi successfully introduced his vision for national healthcare and infrastructure development but clearly compromised many of his earlier reformist ideals in his selection of cabinet members. Duterte conducted a killing spree that has not brought law and order to the country, and he has shown little proclivity for maintaining a populist vision rooted in actual social reform.

Up to now, the performance of these two populist leaders suggests that success at the local level does not necessarily predict success in national politics or policymaking.

—

Ehito Kimura is associate professor and undergraduate chair in the University of Hawaii’s Department of Political Science.

Erik Martinez Kuhonta is associate professor and graduate director in McGill University’s Department of Political Science.

This commentary was provided by The East-West Wire by the Hawaii-based think tank East-West Center. It was first published on Feb. 12, 2018 with the title “Duterte and Jokowi: Do local politics apply?”.